Continuation: the Crusades, the Teutonic Knights, and the Hanseatic League

At the same time as the Xian kingdoms in Spain were starting to reclaim territory from the Moslem Arabs (with the Pope's blessing - in 1063 Alexander II

granted them a standard and automatic absolution of sins for those who fell in battle), the Byzantine Empire was losing to its own Islamic invaders. In 1071

the Byzantines were defeated at the Battle of Manzikert and all of the Middle East except a coastal strip was held by the Seljuk Turks. Emperor Alexios I

appealed to the Pope for aid. Instead of the requested mercenaries, this aid came in the form of the First Crusade, proclaimed by Pope Urban II in 1095. There

was pent-up hatred in Europe of the "Saracens," as they were called at the time: apart from the conflicts in Spain, Italy, and Sicily, the Turks had conquered

Palestine in the 7th century and in 1009 the caliph had ordered the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem destroyed. His successor had allowed the

Byzantines to rebuild it for a hefty price, but meanwhile Xian pilgrims and clergy were captured and killed. Therefore, a major goal of the First Crusade was

recapturing Jerusalem, which was achieved in 1099 after a siege. The Byzantines did not get much support, but in other respects the crusade was a great

success: the Europeans won back considerable territory and established four Crusader States: the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the County of Tripoli, the Principality

of Antioch, and the County of Edessa. Eight further numbered crusades followed, the Ninth Crusade ending in 1272, but none recaptured the glory of the first

and there were some disasters. On the Third Crusade, the Holy Roman Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa drowned in a river and King Richard the Lionheart of England

was shipwrecked and then imprisoned by the Duke of Austria on his way home. The Fourth Crusade turned into a sack of Constantinople and creation of Crusader

states in Byzantine territories because the crusaders did not otherwise have the money to pay the Venetians for their ships. Following that, in 1212 there was

supposedly a Children's Crusade of 37,000 deluded French and German children who all either died or were enslaved by the Turks on their way to Jerusalem.

However, the Crusades did restore some Xian control in the Near East for 200 years, gave fighting men who were no longer as much needed for internal warfare

after the end of the Viking Age and the consolidation of kingdoms something to do other than prey on the populace to get glory, wealth, and power (for example

in 1107-1110 King Sigurd I of Norway, known as Sigurđr Jórsalafari or "Jerusalem-farer," led a successful crusade of Norwegians before the Second Crusade), and

brought back scientific knowledge as well as engineering and military technology such as far stronger castles with round rather than square towers. Also, the

idea gave rise to various expeditions within Europe. Starting in 1209, the French conducted the Albigensian Crusade against the Cathars of the Languedoc, who

adhered to a form of Arian Xianity and had resisted French power. It was in the Second Swedish Crusade (probably in either 1239 or 1256, but for propaganda

purposes it was subsequently backdated to the 1150s and ascribed to St. Eric) that Sweden annexed most of Finland, which would remain Swedish property until it

became Russian at the end of the 19th century. The Swedes converted the pagan Finns and Sami and extended agriculture north into formerly nomad-inhabited

lands. Finally at the end of the Middle Ages, in the 15th century, there was a crusade against the proto-Protestant followers of Jan Hus in Bohemia and a

series of crusades in the Balkans against the Ottoman Turks.

Most crucially for the Germanic world, the defeat of the Byzantine Empire and the Crusades led to the establishment pf military orders: in 1080 the Knights

Hospitaller (or Knights of Malta, or Knights of St. John) to care for sick and injured pilgrims to Jerusalem; in 1118 the Knights Templars to fight in the

Crusades and to care for Crusaders' assets while they fought (which led to their becoming the bankers of Europe and immensely wealthy); and in particular in

1190 the Teutonic Knights, originally formed in Acre to assist pilgrims.

After the Moslems reestablished control in the Middle East, the Teutonic Knights transferred their activities to rooting out paganism in Europe, starting in

Hungary in the early 13th century. In 1230 they spearheaded the Prussian Crusade, to convert the Wends in the lands between the Elbe and Poland . . . and pave

the way for German settlement there. They set up their own country, the Monastic State of the Teutonic Knights, and went on to conquer and convert Courland,

Livonia, and Estonia. This is the origin of Saxony - settled by Saxons from what is now called Lower Saxony (Niedersachsen) who blended with the Slavic Wends

as they converted, and known as the March of Meissen until the rulers of Meissen acquired control of the Duchy of Saxony in 1423 and decided to call the whole

of their kingdom Saxony - and of the March (Mark) of Brandenburg, the nucleus of Prussia. In both of these, "march" means a frontier region.

The Teutonic Knights became immensely wealthy from the feudal income from their lands, hired mercenaries from all over Europe, became a naval power in the

Baltic, and assimilated other, smaller orders. They were so aggressive that they came into conflict with existing Xian states such as Poland and Lithuania, who

saw them as encroaching on their territories. In 1410, they were trounced by a joint Polish-Lithuanian army at the Battle of Grunwald or Tannenberg, but their

power was only truly limited a century later: in 1515 the Holy Roman Emperor withdrew his political support after marrying a polish-Lithuanian princess, and

then they lost large areas to Protestantism, starting in 1525 when their own Grand Master Albert of Brandenburg converted to Lutheranism, resigned, and became

Duke of Prussia. (They hung on in Catholic areas until Napoleon stripped them of their holdings in 1809 and are now a purely charitable order.)

In the meantime, their activities had led to the extension of Germany deep into Slavic territory, to the borders of Poland, and more scattered settlement of

Saxons from the Upper Harz and Westphalia in the ore-rich areas of Southeastern Europe: in modern northwestern Bulgaria (where the Banat Bulgarians and

Krashovani are thought to be descended from them), in what is now the Czech Republic, and in Serbia, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina. (They also

supposedly spread the rabbit, by giving them as gifts to noblemen.) The Slav areas settled by Germans in the Middle Ages are sometimes referred to as Germania

Slavica, "Slavic Germania," and the movement of settlers in the High Middle Ages as a result of the knights' activities is known in German as the Ostsiedlung,

"eastern settlement." (There was a later wave that took German settlers to Russia to become the "Volga Germans" after Catherine the Great, who was German by

birth, invited them on favorable terms to create farms and to separate her subjects from the nomadic peoples of Asiatic Russia.)

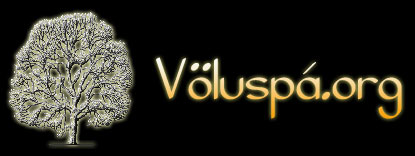

Furthest extent of power of the Teutonic Knights

Map created by Space Cadet at the English language Wikipedia [GFDL ()], via

Wikimedia Commons

Alongside the Teutonic Knights, another factor in extending German power and settlement to the east was the Hanseatic League (in German simply Hanse or

Hansa, a word that means "guild"). This was an association of merchant cities that protected each other and had their own laws. Those within modern Germany

have retained some degree of autonomy: Bremen, Lübeck, and Hamburg still call themselves "free Hansa cities" and are their own states within the republic.

The origins of the group seem to lie in the rebuilding of Lübeck in 1159 after Henry the Lion of Saxony had captured it from the Count of Holstein, and Lübeck

was the most prominent of the Hanseatic cities and the location of the periodic member meetings or Hanseatic Diets. By negotiating with rulers for relaxation

of tariffs, providing mutual protection against piracy and other threats (they maintained a navy, trained pilots, and constructed lighthouses), and allying

with Swedish merchants to take over the trade with the lands of the Kievan Rus (Novgorod became their easternmost outpost), they greatly built up trade in the

Baltic and created a wealthy middle class. Some of the cities in the league, such as Elbing, now Elblag, had been founded by the Teutonic Knights; others,

such as Danzig, now Gdansk, and Riga were developed directly as Hanseatic trading posts. Some were under "Lübeck Law," which required all disputes to be

referred for adjudication to the city council of Lübeck; some were "free imperial cities," directly subject to the Holy Roman Emperor; and there were also

trading centers, known as counting-houses or "Kontors," that were walled enclaves within cities such as London and Edinburgh. The Hanseatic merchants and the

Low German dialect in which they did business had a considerable effect on Scandinavia, in particular. At the height of its power, the League went to war

against Denmark and won: in 1368 they sacked Copenhagen and Helsingborg, and under the treaty of Stralsund King Valdemar IV of Denmark and his son-in-law Hakon

VI of Norway granted the League 15% of the profits from Danish trade in the subsequent peace-treaty of Stralsund in 1370. This gave them an effective monopoly

of Scandinavian trade, and in 1435 another treaty renewed the arrangement. The monopoly was only broken by another war: in the Dutch-Hanseatic War (1438—41),

the merchants of Amsterdam won free access to the Baltic. Disputes among members and the hostility and rival trading activity of nation-states led the League

to become much weaker in the 16th century and eventually be dissolved in 1862, with only three member cities; it had peaked at over 100.

Map of Hanseatic cities and Kontors

By Credited as London: Wm Heinemann [Public domain], Wikimedia Commons

[1. Teutonic Order State image from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Teutonic_state_1455.png

2. Extent of the Hansa image from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Extent_of_the_Hansa.jpg]

|